Continuing the legal translation series, it seems fitting to discuss a topic that overlaps with both the family registry in Japan (i.e. 戸籍 koseki) and contracts. While I admit my views on this are neither romantic nor religious (nor of the kind that my husband enjoys hearing), marriage is simply a relationship bound by a legal contract, and as such, it contains a break clause: namely, an annulment or divorce. Divorce in Japan, and particularly in the United States, is a complicated and emotional process, made even more so when language barriers and societal differences in laws and social customs are involved. Let’s take a closer look at the differences between divorce in Japan and the USA and the role of a translator or interpreter within this process.

Divorce Statistics

Divorce is not uncommon in either Japan nor the United States of America. In my own country people throw around the phrase “half of marriages end in divorce”, often with a pejorative connotation indicating the breakdown of so-called “family values”, while in Japan the fact that one in three married couples get divorced, a rate not far behind the United States, has gotten more attention to the point of being a topic of discussion by quasi-celebrities on variety shows. While both general trends and societal attitudes towards divorce can be observed in these approximate figures and the tone in which they’re presented, government statistics provide a better source for comparing divorce trends in the USA and Japan, which share an overarching pattern.

According to the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, there were 207,000 divorces in Japan in 2017 with 1.6 divorces per 1000 of the population, which has been declining since its peak of 2.3 in 2002. Meanwhile in the United States, according to the CDC, the were a total of 787,251 divorces or 2.9 per 1000 of the population in the United States in 2017, down from 4.0 in 2000 and 2001. However, it is meaningful to note in the comparison of these divorce rates that the 2017 marriage rate was 4.9 per 1000 in Japan compared to 6.9 in the United States, both of which are slowly declining. To put it simply, both marriage, which is necessary to file for divorce, and divorce are currently in gradual decline both Japan and the USA.

Divorce Procedures

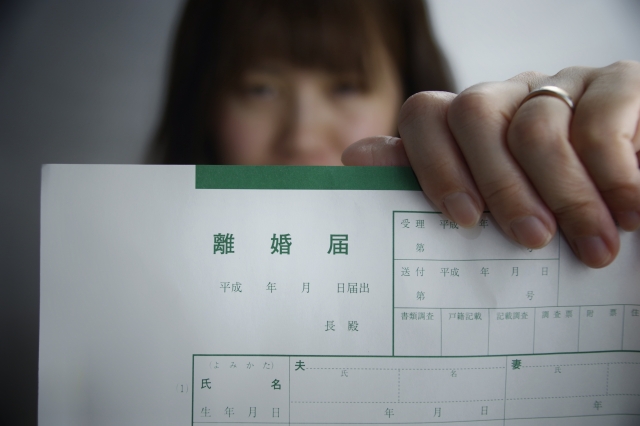

While divorce is common in both the United States and Japan, the procedures and legal framework are quite different in the two countries. This changes what documents require translation and what venues require an interpreter. Foreign residents can get divorced in their country of residence, but in doing so they must follow the procedures of that country, which necessitates the translation of key documents (i.e the Divorce Petition (離婚申請書) and accompanying documents in the USA or the 離婚届 (Divorce Registration) in Japan, as well as the Marriage Certificate or 婚姻届 ).

One major difference is that in the “litigious country of the United States” (《起訴ずきの国》アメリカ ), as Attorney Michiko Ito describes it in her book 「アメリカ駐在員のための法律常識 Amerika chuuzaiin no tame no houritsu joushiki」(Practical Law for Japanese Businessmen in America), both parties must appear in court and the divorce cannot be finalized without the approval of a judge. As the USA has found that a hearing is invalid if the defendant cannot understand English, the court must provide an interpreter for Non-English Speaking (NES) or Limited English Proficiency (LEP) petitioner or defendant. Meanwhile, one major difference in Japan is the relevance of the Family Registry, a multi-purpose document explained in a previous post. If one party is of Japanese nationality, whether residing in the USA or Japan, or is married to a Japanese national or a foreigner, they must update the family registry, including translating any required official documents for evidence, once the couple has completed divorce procedures and has finalized the divorce, regardless of the jurisdiction.

Divorce Procedures in Japan

In Japan, the Domestic Relations Case Procedure Act (家事事件手続法 )contains the laws that govern divorce procedures. The divorce must be mutual (i.e. not contested) and the couple must come to an agreement about the distribution of property(資産分与), child custody (親権), child support(養育費), and settlement or consolation money(慰謝料)before it’s finalized. The process puts more emphasis on salvaging the relationship and cooperation.

How complicated this is depends on the type of divorce, whether they have children, and whether one spouse had an affair, which necessitates consolation money. Joint custody ends with the marriage and typically custody goes to the mother, but that is negotiable along with how much child support the other spouse should contribute and whether or not to split assets 50/50 or 40/60 etc.

There are four types of divorce in Japan, which range from being mainly administrative procedures to court mandated decisions.

- Divorce by mutual agreement(協議離婚)According to Attorney Umezawa in his article on the Divorce Lawyer Navigator website, about 90% of divorces in Japan are this type, in which the couple agree to divorce, regardless of the grounds for the divorce, and fill out the Divorce Registration (離婚届)to submit it to their local municipal office.

- Divorce by mediation (調停離婚)If the couple can’t agree on the details of the divorce or agree to divorce, the next step is mediation through a court-appointed family councilor. This step is detailed under the Principle of Conciliation First in Article 255 of the Domestic Relations Case Procedure ( 家事事件手続法255条 調停前置主義 ), with the only exception to this step being cases of domestic violence. It takes two to four weeks to get an appointment with the councilor and the process can take anywhere from a month to a year. Legal representatives of either party are allowed to participate in the mediation sessions and mediation may lead to the couple staying married or making concessions about the details of the divorce.

- Divorce by the decision of family court(審判離婚)If the couple cannot come to an agreement through a family councilor, the case enters family court as detailed in Article 284 and the judge determines an equitable solution. Although according to Mr. Hagihara at Legal Mall, only about 0.1% of divorces are settled in this way.

- Divorce by the decision of a district court (裁判離婚)However, if one party disagrees with the family court decision or finds it inequitable, the case enters a district court in a longer evidence-based court process.

While the overall process is easier, there are varying points in which a translator or interpreter, or an attorney, may be necessary. If one party were to get re-married in another country or needed to prove their marital status (like for immigration), a translation of the Divorce Registration would be required. In the case of an international marriage, in which one party is not fluent enough in Japanese to comprehend legalese, then an interpreter would be required for mediation or court, in addition to a translation of court documents and the initial Divorce Registration.

Divorce Procedures in America

Any legal or administrative procedure is made more complicated in the USA due to the lack of legal consistency throughout the country, as each state is considered sovereign allowing it to create, implement, and enforce its own laws. In contrast to Japan, which simply requires couples to fill out and submit a two-page administrative document, one thing that unifies all states in the US is how complicated the overall divorce procedure is.

All states technically recognize a no-fault divorce. In these cases, the grounds for divorce are often “irreconcilable differences” or an “irreparable breakdown of the marriage.” Yet to make this more complicated, some states require the spouses to live apart for a certain period of time before divorcing, except in a ‘fault’ divorce, i.e. divorce under the grounds of adultery, confinement, physical or emotional abuse, abandonment, or a sexless marriage. (Check out Findlaw for more on these two types of divorce.)

As Legalzoom elucidates, most of the USA does conform to the following procedures, although specific details and extra documents which are needed may change.

- One spouse (called the ‘petitioner’) fills out a Divorce Petition, a document that indicates the couple’s name and if they have children, and lists any property, child custody, or child support.

- This petition is served to the other spouse, which is called a Service of Process. The other spouse (called the ‘respondent’) can sign it if they agree.

- The respondent has 30 days to file a response to the petition. In that time period, neither spouse is allowed to take the children out of state or sell/lend their property or insurance.

- The spouses must disclose their assets, liabilities, income, and expenses, and create a parenting plan for any children they have. A parenting plan details who makes final decisions for education, major medical issues, extra-curricular activities, and religion etc, which parent has primary custody, the division of physical custody and child support. Any prenuptial agreements entered into will effect the divisions of assets.

- Assuming the divorce isn’t contested, the judge has the final say. The court gives a judgement determining if the distribution of assets is fair, if the parenting plan is in the child’s best interests, and if there are any reasons not to dissolve the marriage (such as pregnancy or co-habitation).

- If it’s contested, then this will enter more court hearings or even a trial.

The general process in the US is inherently more combative than in Japan and provides more opportunities for both language professionals and legal professionals to guide couples along the labyrinth which is US Family Law in each state.

In a simple divorce proceeding with at least one party who is not fluent in English, the court will provide an interpreter for the judgement, the mandatory parenting class if that states requires it (now required in Illinois for both the male and female parent), and any family mediation provided by the court. In Cook County, IL, where I live, couples are allowed two three-hour sessions of mediation, in which a mediator discusses the parenting plan only. If one spouse is Japanese, the Divorce Certificate must be translated to update the Family Register (戸籍). However, one spouse may want to commission the translation of all court documents including those verifying assets, liabilities, and the parenting plan.

In more complicated cases which are contested, the court may have to do discovery, the legal process of finding evidence for trial, related to the couple’s assets, child support, criminal records, etc. Any records in a foreign language which require translation and discovery through court-ordered interrogatories also require an interpreter for non-proficient English-speakers.

Parental Kidnapping and the Hague Convention

While a marriage does not necessitate children, their presence in any form of break-up complicates everything. Whether in Japan or the US, the divorce procedure focuses on finances and children. In the case of an international divorce (or in the US even a cross-state divorce), there is a new dimension brought in. Namely, if both parents live far away, who will the children stay with? And when will the other parent get to see their child?

Imagine this scenario. Let’s say mom and dad live in New York, where mom is from, and dad has immigrated to the USA from Japan. They have one child living with them who is a minor. The marriage is falling apart and they decide to divorce, but dad wants to go home to Osaka. It’s hardly in the interest of the child to spend every other week in a different country. Both parents want the child to live with them. Who does the child stay with? And what happens if dad takes the child to Japan without informing mom? Alternatively, what if the family lived in Osaka and mom wanted to go home to New York with their child, so she took a flight to the USA without talking to dad?

This is referred colloquially as parental kidnapping. The international treaty dealing with these issues is the Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction(国際的な子の奪取の民事上の側面に関する条約), also referred to as the Hague Convention (ハーグ条約). Both the USA and Japan have signed and ratified the Hague Convention, the USA in 1994 and Japan in 2014. Simply put, the Hague Convention is an agreement to work internationally on a country-by-country basis to make sure one parent is not allowed to disappear with the child.

Let’s take a brief look at the convention itself to see how it would play a role in international divorce cases.

Article 1 Objectives (第一条 目的)

- Prompt return of children wrongfully removed or retained (不法に連れ去られ、又は不法に留置されている子の迅速な返還)

- Rights of custody and of access (監護の権利や接触の権利)

Much like in the USA, where children are not allowed to leave their state of residence during the divorce, the Hague Convention stipulates that children must stay in their habitual residence (常居所), which is where they were living prior to the procedure, unless both parents agree to change the habitual residence. As to custody and access, it’s worthwhile to note the major difference in thinking between custody in the USA and Japan. As previously mentioned, in Japan sole custody is the norm with the other parent providing child support, whereas in the USA, joint custody is more common, although how that’s enacted varies drastically. The Hague Convention itself does not define who has custody or access, as this is enforced between individual countries.

Parents whose children have been internationally abducted can file a Hague Application, providing the child is under 16, but any documents submitted in a foreign language require translation. In addition, if the case goes to court in any country, interpreters must be provided.

For more about the specific language of and translation related to the Hague Convention, I highly recommend any JAT members to watch Hideaki Maruoka’s session at the I-JET30 Conference, which was illuminating on this issue.

Dissolving the Union

As international relationships become more common, it’s no surprise their antithesis is becoming more common as well. Personally, I see no use in moralizing about this. While relationships are a beautiful part of life, so is being able to leave a toxic one.

Language professionals have an important role in this process as a third party to keep communication from breaking down entirely, whether in person or in writing. While the interpreter is not an advocate for those they interpret for, speaking from my own experience interpreting for divorce mediation and a final divorce hearing, an interpreter has a pivotal role in ensuring foreign-language speakers can understand what is going on in this tricky, complicated process. Likewise, having translated divorce documents related to the Family Register, while there is more of an emotional separation, this too is imperative to ensure both parties fully understand and have a legal record of their current marital status. Understanding both systems is imperative as a language professional, and immensely useful as an attorney with a foreign client or someone going through an international divorce.

Both systems have their issues. The system in Japan puts more focus on the partners coming together to agreements, which does allow the potential for one to have more power. Conversely, the USA assumes divorce is a combative process, in which communication has already broken down, necessitating judges, attorneys, and mediators act as a go-between for the couple. This can make even a mutual and amicable split-up strained and extremely expensive. The breakdown of a relationship is an emotional process, which can be made worse by a combative process or one that allows one partner to potentially take advantage of the other. As an international community it’s important to understand the laws that bind us and the faults within them. After all, customs and procedures can always be reformed.